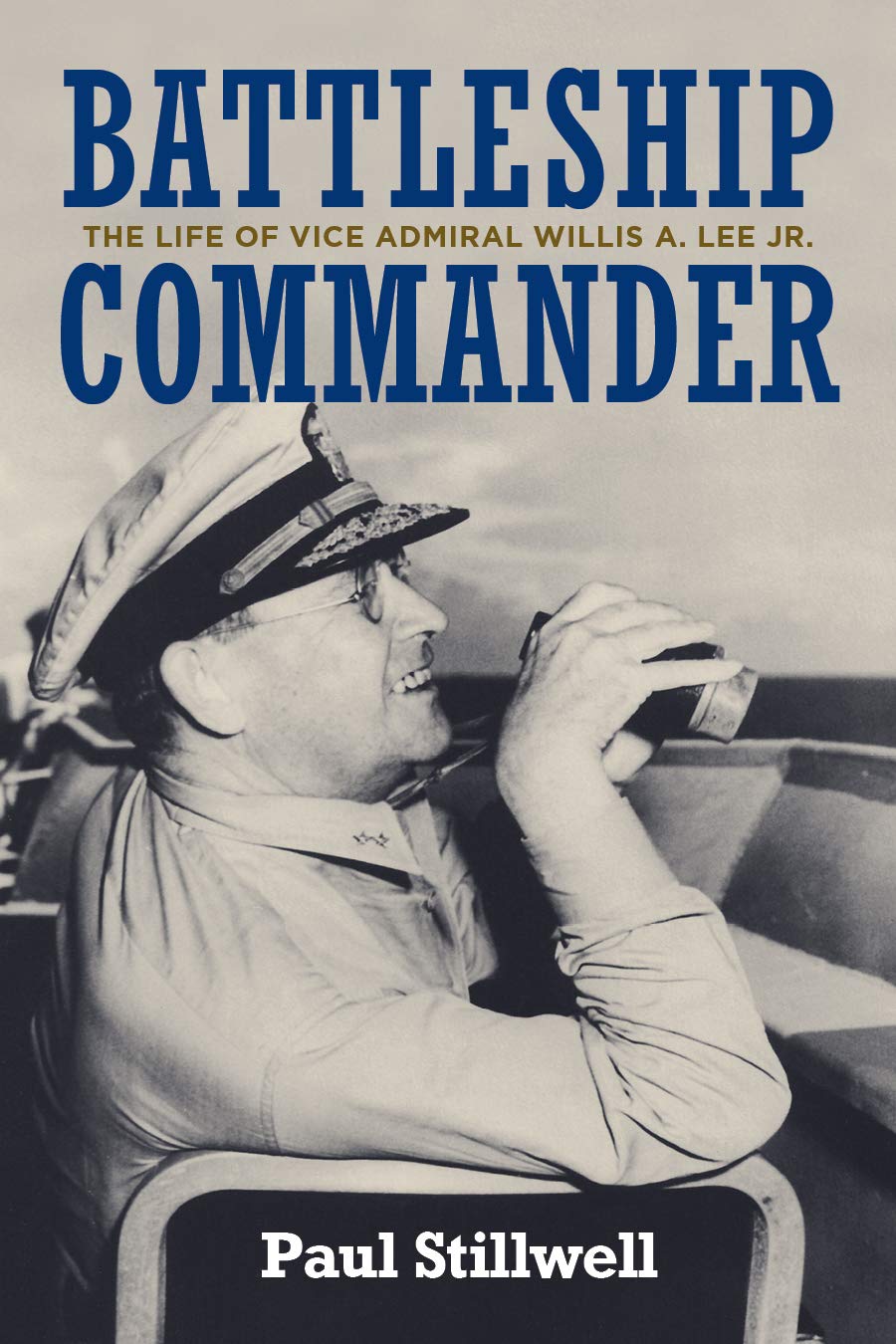

Battleship Commander: The Life of Vice-Admiral Willis A. Lee, Jr.

Paul Stillwell

Willis Lee was the victor at the Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal where the battleship Washington sank the Japanese dreadnought Kirishima. He is best known for announcement of his arrival. Using his academy nickname in a plain-text broadcast to PT boats in the area he said: “Peter Tare [PT] this is Ching Lee. Chinese. Ching Lee, catchee? Stand clear, we are coming through.” Politically incorrect today, it was a coded reference his fellow naval officers understood, but the Japanese would not. The battleships had arrived.

Willis Lee was the victor at the Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal where the battleship Washington sank the Japanese dreadnought Kirishima. He is best known for announcement of his arrival. Using his academy nickname in a plain-text broadcast to PT boats in the area he said: “Peter Tare [PT] this is Ching Lee. Chinese. Ching Lee, catchee? Stand clear, we are coming through.” Politically incorrect today, it was a coded reference his fellow naval officers understood, but the Japanese would not. The battleships had arrived.

Battleship Commander: The Life of Vice Admiral Willis A Lee, by Paul Stillwell, is a new biography of Lee. It is the first serious biography of Lee, perhaps the best battleship commander and admiral the United States Navy ever had. The book, an outstanding treatment of Lee’s life, was worth the wait.

Stillwell’s examination of Lee’s life is comprehensive, covering both his professional and personal life with great attention to detail. Stillwell takes the story from Lee’s bucolic Kentucky childhood through the Naval Academy and into his career as a naval officer. It ends with Lee’s death while commanding Task Force 69 at Casco Bay, Maine, researching kamikaze defenses.

Lee is revealed as a man of many dimensions. A crack marksman, despite myopia, he won more shooting medals (including eight at the 1920 Olympics) than any other naval officer. He acted as a sniper during the 1914 Vera Cruz incident. Stillwell reveals Lee as a man with incredible attention to technical detail, serving as inspector of ordinance during his early career and the Fleet Training Division in Washington just before World War II. Lee was an equally outstanding ship’s captain during stints commanding the destroyer Lardner and light cruiser Concord.

Stillwell also reveals the many surprising ways in which Lee helped position the United States Navy for victory in World War II. Pre-war, while in Washington D.C. Lee helped steer resources away from building additional Alaska-class cruisers, and towards building more aircraft carriers. More importantly, he championed increased antiaircraft defense, including championing adding the Sperry Gunsight, the 20-millimeter Oerlikon and 40-millimeter Bofors to Navy vessels.

While commanding battleships in the Pacific, Lee was a strong radar advocate, helped pioneer the combat information center and was one of the first to see the potential of the proximity fuze. His efforts were instrumental in having it available for use against kamikazes.

One of the strengths of this book is Stillwell’s ability to put the events of Lee’s life into a historical context. Stillwell explains what is going on during different periods of Lee’s Navy career and how and why they affected Lee and the decisions Lee made. He also intersperses the book with those with whom Lee impinged, famous for events unrelated to Lee. Among them are James Van Allen, Sergeant Shriver, and Herman Wouk.

Battleship Commander is well-researched, and well-written. The descriptions of the battles Lee fought are fast-paced and exciting. It is a highly informative account of a man whose naval career has been long underappreciated.

- Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2021

- 6-3/4” x 9-3/4”, hardcover, xvii + 336 pages

- Illustrations, notes, bibliography, index. $37.95

- ISBN: 9781682475935

Reviewed by: Mark Lardas, League City, Texas