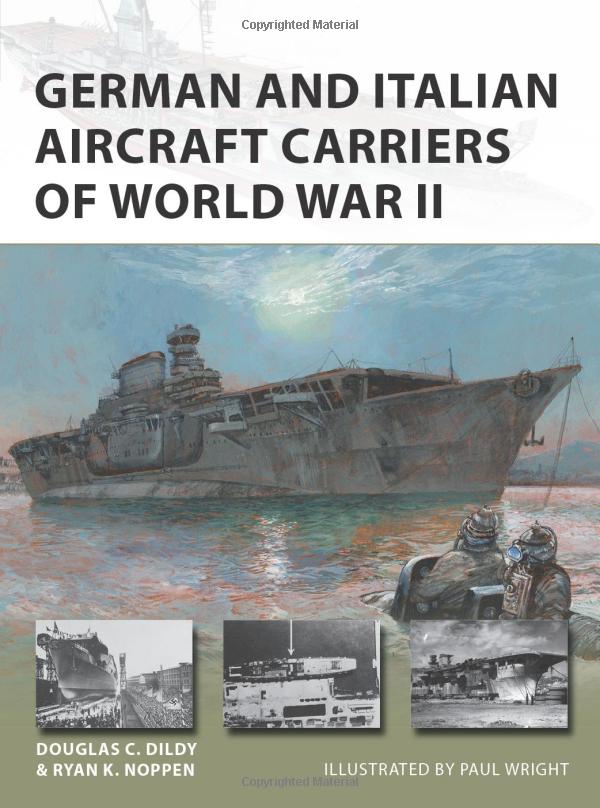

German and Italian Aircraft Carriers of World War II

By Douglas C. Dildy & Ryan K. Noppen

German and Italian Aircraft Carriers of World War II, by Douglas C. Dildy and Ryan K. Noppen dives into the aborted efforts of these two Axis powers to create a seagoing air arm to combat England in the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

German and Italian Aircraft Carriers of World War II, by Douglas C. Dildy and Ryan K. Noppen dives into the aborted efforts of these two Axis powers to create a seagoing air arm to combat England in the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

Forty-eight pages, packed with period photographs, color artwork, and a fast-moving text tell the story in chronological fashion, starting with German efforts in World War I to create seaplane carriers for scouting purposes, due to the slow speed of the Zeppelin airships in this role. Very surprising is the early plan for an actual aircraft carrier, Ausonia, a converted ocean liner envisaged in 1918! Events, of course, ended that plan, but the seed of the ocean liner-to-carrier conversion idea were planted, and there is a full-color rendering of Europa, a 1942 conversion that was eventually cancelled due to the reduction of performance that such a conversion would have resulted in.

The authors move on to Nazi Germany’s Plan Z, which called for a true flush-decked fleet carrier, Graf Zeppelin, which was laid down, and proceeded to about 85-percent completion before war’s end. The authors lavish some detail on this ship, its construction, and the turmoil that eventually sealed its fate. There is a section on the proposed aircraft for this carrier, Bf 109T (Toni) fighters, Ju 87C-0 dive bombers (with folding wings), and Arado Ar 96B-1 naval trainers. There is even mention (and a rare photograph) of the proposed Me 155 shipboard fighter—I had never seen this before.

Two more proposed converted carriers, Elbe and Weser are covered briefly, with color renderings and concise information. Other considered projects are mentioned, and all then comes to a screeching halt with an order from Hitler stopping all work on these (and other) ships. This effectively brought Nazi Germany’s aircraft carrier projects to a close.

The authors move on to Italy next, and we meet the very forward thinking 1920s Italian Navy Chief of Staff, Thaon di Revel, who envisioned conversion of battleships into flush-decked aircraft carriers as far back as the early 1920s. Although several conversions were indeed started, and others planned, the rise of Mussolini soon aborted the projects. The Regia Aeronautica had full control of air matters, and its leadership had no interest in aircraft carriers. Italy did have an operational seaplane carrier, Giuseppe Miraglia, but it was very limited in capability.

The pressure of a losing war against Britain finally forced the Italians to begin conversion of a liner, Roma, into the fleet carrier Aquila (Eagle). Superficially similar in appearance to Graf Zeppelin, Aquila was an ambitious design, and was to have had radar and an air group of about fifty aircraft. Much German technology was incorporated, as the Italians had no experience in building carriers. Italy’s collapse in 1943, however, ended the project.

This volume, although compact, is fascinating reading, and contains details I had never known about the events and people surrounding these mysterious ships. Many pictures were new to me, and the statistics are presented in a clear, understandable format. Recommended!

- Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2022

- 7-1/4” x 9-3/4”, softcover, 48 pages

- Illustrations, bibliography, index. $19.00

- ISBN: 9781472846761

Reviewed by: Rick Cotton, Katy, Texas