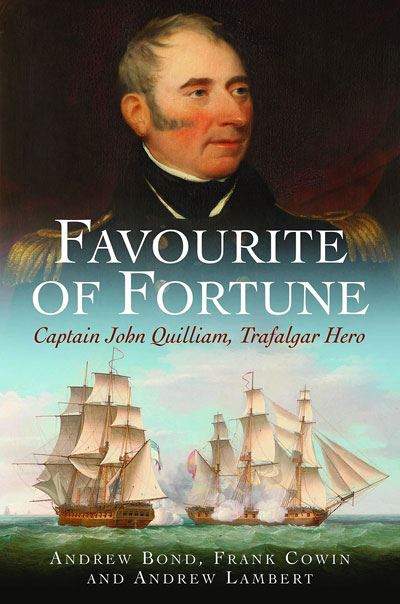

Favourite of Fortune: Captain John Quilliam, Trafalgar Hero

Andrew Bond, Frank Cowan& Andrew Lambert

In introducing John Quilliam, a Trafalgar hero, to readers, Bond, Cowin, and Lambert state “that Quilliam is so little known in the wider world is all the more remarkable, given his extraordinary career, which can compared with those of the great heroes of naval fiction, Hornblower and Aubrey.” That may be the case for the wider world, but for members of The 1805 Club, Quilliam is a known entity, and held in high regard.

In introducing John Quilliam, a Trafalgar hero, to readers, Bond, Cowin, and Lambert state “that Quilliam is so little known in the wider world is all the more remarkable, given his extraordinary career, which can compared with those of the great heroes of naval fiction, Hornblower and Aubrey.” That may be the case for the wider world, but for members of The 1805 Club, Quilliam is a known entity, and held in high regard.

In John Marshall’s Royal Navy Biography (1825), the only other biography written about Quilliam, we learn that “This officer may be truly styled a favorite of Fortune.” Bond, Cowin, and Lambert confirm this assessment.

The authors trace Quilliam’s life from the island of his birth, the Isle of Man, through his service in the Royal Navy, to his return to his birthplace as a man considered by his fellow islanders as “Manx Worthy.”

He entered the service at the age of seventeen in 1785 and worked in the Portsmouth Dockyard. Quilliam was rated as an able seaman, which indicates he had previous experience at sea. As he rose through the ranks he would draw on his dockyard knowledge.

In 1792, he joined his first ship, the third-rate HMS Lion (64) and sailed to China. The objective of the cruise was to extend diplomatic relations with the emperor of China. Captain (later Admiral) Sir Erasmus Gower looked favorably on Quilliam: “Lion’s voyage to China had transformed him into a man-of-war’s man, Britain’s most important resource in her hour of need, and secured him the support of the Royal Navy’s senior captains.” The authors show that patronage from senior officers, such as Erasmus, James Gambier and Horatio Nelson, was helpful in Quilliam’s promotion prospects. Promotion through patronage was a common practice throughout the fleet. However, as in other historical analyses found in From Across the Sea: North Americans in Nelson’s Navy, an officer’s chance of promotion finally came down to performance. Quilliam had it in spades.

Quilliam next transferred to the third-rate HMS Triumph (74), again under Captain Gower, who promoted him to quartermaster’s mate; a rank often interchangeable with that of midshipman. Although another captain replaced Gower before Triumph fought at the Battle of Camperdown, it appears Gower was greatly impressed by Quilliam’s performance during the battle and had him transferred to his own ship, the second-rate HMS Neptune (98) as acting lieutenant. Quilliam was aboard for only twenty days, having to transfer again, because he had been promoted to lieutenant.

With his transfer to a sloop-of-war, Quilliam’s professional life would, for the most part (except for being aboard Victory at Trafalgar), center on serving in and commanding Royal Navy frigates. He rose to post captain and acquired wealth from prize money.

As second lieutenant, Quilliam applied his ‘dockyard matey’ skills at the Battle of Copenhagen, in which he quickly restored his damaged frigate to fighting trim. As a result of his performance at Copenhagen, Nelson selected him above other lieutenants to be Victory’s first lieutenant. His performance during Trafalgar and its aftermath ensured Victory survived the battle and the subsequent storm; despite, sadly, the loss of his benefactor.

Quilliam returned to frigates as a post captain and served in the Baltic, where he successfully escorted critical naval store convoys from Sweden. The Baltic Fleet commander, Admiral Sir James Saumarez noticed his performance, and gave Quilliam command of two additional frigates.

However, good deeds do not necessarily go unpunished. When Quilliam commanded a frigate on the Newfoundland Station during the War of 1812, his first lieutenant charged him with cowardice for not engaging what might have been one of the United States Navy’s ‘super’ frigates. Quilliam’s charge for cowardice was dropped, together with lesser charges brought forward by his subordinate. The reader will find it interesting to note why Quilliam even faced court martial in the first place.

Quilliam returned to sea during the waning months of the Anglo-French War and the American War, performing his role as a talented convoy escort commander in the Caribbean. With the peace, he returned to his island home. He regained his seat in the House of Keys and married a local heiress (although he was quite well off himself). Both were in their late 40s at the time. He was active in improving the island’s fisheries and reducing the loss of life resulting in the many shipwrecks in Manx waters. Quilliam can be called the father of what is now the Royal National Lifeboat Institution.

This biography is a worthy read about a Royal Navy officer who was rather unique in his profession; not only a master at commanding a sailing man-of-war at sea and in combat, but also a master of the technology of building, maintaining and refitting the complex machinery of sailing warships. He was “truly styled a favourite of Fortune.”

- Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime, 2021

- Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2021

- 6-1/2” x 9-1/2”, hardcover, xvi + 181 pages

- Illustrations, maps, notes, glossary, index. $44.95

- ISBN: 9781399012706

Reviewed by John A. Rodgaard, Melbourne, Florida